Image credit Explaining the Future.

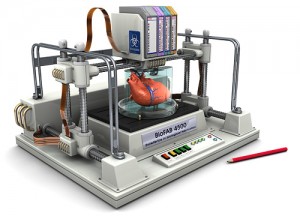

So far, the topics we’ve discussed have involved inorganic, “dead” materials. Printed items are made out of foam, plastic, latex, or a similar material. But what if you could print something that was alive, or had the potential to be? What if you could print a flower, or a piece of meat? This process exists, and it’s called bioprinting.

How it Works:

Take a look at your arm. From your point of view, your arm is a solid object; you can touch the surface of it, and you certainly can’t move through it.

But if you put your arm under a microscope, you’d notice that your arm isn’t actually solid at all. It’s composed of billions upon billions of tiny cells, layered and structured perfectly to make the biological organism that is your body.

Bioprinting is essentially just printing with cells. Cartridges are loaded with living cells, contained in incredibly tiny clusters. The printer releases the cells into a protective, dissolvable gel, which keeps them from dying during the printing process. Just like a plastic object, the organ is built up layer by layer.

This technology is currently still in its preliminary stages. Human blood cells and simple pieces of tissue have been printed, but nothing more. But in a handful of years, there’s a good chance that bioprinting technology will become mainstream.

Printing Organs

The most obvious use of this technology is to create replacement organs for transplant. There would be no more need to wait for years on the transplant list, hoping that a matching organ becomes available. Instead, a culture of your own cells could be used to make a perfectly matching heart, kidney, or liver – with little risk of rejection.

Technology like this could also be used to replace body parts that we currently can’t transplant. Last week, we talked about skull transplants and other prosthetics. With bioprinting, the door is opened even wider; you could print a new eye, a new piece of skull, or even an entire leg.

The current leader in this field is Organovo, a company that prints human tissue for use in research and medical therapy. No, you can’t get a printed heart just yet – but in 5 years, who knows?

Printing Meat

Another use for bioprinting that’s in the works is the printing of meat for consumption. Instead of getting your burger from a cow, the scientists over at Modern Meadow hope that you’ll be able to get it from one of their labs.

Printed meat would have a huge impact on both the environment and global hunger. Without needing land to support billions of cattle, there would be no need to demolish rainforests and other natural areas. Likewise, if meat can be produced cheaply and efficiently, it could become far more affordable for the average person.

As with organs, printed meat is still in the works. The researchers behind it are currently trying to get the right combination of fat and muscle cells to help create that “meat” taste. After that, it’s simply a matter of figuring out how to print food on a massive scale.

What Would You Do with Bioprinting?

With the ability to print layers of living cells, there’s practically no limit to what you could make. Feel like a steak for dinner? Print it. Want a salad to go with it? You’ll probably be able to print that too. Accidentally cut yourself with the steak knife? Christopher Barnatt at Explaining the Future believes that one day, we’ll be able to print living skin cells right onto a wound, healing it almost instantly.

The ability to print and layer cells also opens up amazing research possibilities. We will be able to study different cell combinations. Maybe one day, we’ll even have the ability to actually create living organisms, printed in a lab.

So, what would you do if you had a bioprinter? We’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.